The municipality of Dragør has moved away from an ‘insensitive’ coastal defences policy Instead, the municipality has chosen nature’s own technology for adaptation to the climate of the future.

With a mere 13,000 inhabitants, the municipality of Dragør is one of Denmark's smallest municipalities. It covers the southern tip of the island of Amager close to Copenhagen Airport. Both the crooked streets of Dragør and the surrounding beach meadows, rich in animal and plant life, are favourite days out for people living in the region.

The municipality is very low-lying and therefore vulnerable to both sea and groundwater level increases, extreme precipitation and storm surge events. The people of Dragør have been well aware of this for generations. They have learned to live with the fact that sometimes there is too much water, both in the city and in the open countryside. Therefore, the people of Dragør have built dykes around the cities and established large delay basins along the coast.

The municipal structural reform got things going

In recent years, however, there has been a number of incidents which have made politicians, civil engineers, and spatial planners in the municipality think long and hard about climate change and make visionary and concrete plans for the new climate conditions of the future.

"When the responsibility for spatial planning of the open countryside was transferred to us as a part of the municipal structural reform in 2007, the entire southern part of Amager suddenly became our responsibility, where the entire coastal zone is an international nature conservation site (Natura 2000). On top of this there were the plans to raise the dyke protecting western Amager; plans that would also influence decisions on future coastal defence structures in Dragør," says Jørgen Jensen, who is head of Plan og Byg (spatial planning and building) in the municipality of Dragør.

At about the same time, underpinned by the future scenarios from the UN's IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), climate change reached the top of the agenda, and the scenarios were made pertinent when Dragør was hit by a powerful rainstorm in the summer of 2007, bringing some 58mm of rain to the area in a single day.

Nature as the unifying force

In other words, the municipality of Dragør faces having to coordinate a great number of different factors and considerations in their future planning efforts.

"We pretty quickly summarised the material assets as being rather limited and concluded that the rich nature and recreational areas of Dragør were to be the unifying force in our planning. We also decided to turn the problems associated with climate change around, into something positive, and to see them as an opportunity to incorporate the increased rainfall amounts and water levels, nature, history and culture into an entirely new vision for the landscape of southern Amager," Jørgen Jensen explains.

The municipality's "Planstrategi 2007" (spatial planning strategy 2007) therefore contains a special section on climate change. In December 2008 the strategy was followed up by a "Grøn blå plan" (green blue plan), which summarises the most important topics on the open countryside. Finally in June 2009, the municipality published its local climate strategy.

Avoiding an 'insensitive' coastal defence policy

The great idea behind the municipality's green blue plan and local climate strategy is to avoid an 'insensitive' coastal defence policy and instead to employ nature's own technology and to some extent allow nature to adapt to altered climate conditions on its own.

"The concept of allowing the biodiversity that exists in our beach meadows to spread inland is very exciting. This is of course a controversial concept, because it means that in the long run farmers will have to abandon some of their farmland, but it will provide Dragør with entirely new recreational opportunities. There is also the possibility of coastal defences that accommodate beach meadow biotopes dependant on occasional flooding," says Jørgen Jensen.

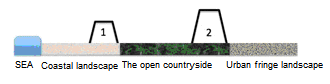

Two types of dyke are being planned. Dyke type 1 are typically recreational dykes and dykes along ditches and forest fringes. These dykes are designed in harmony with the landscape and will overflow during extreme water levels and storms. This consideration for the landscape means that type 1 dykes are not as high as type 2 dykes, which are constructed to protect housing areas, public roads etc. (Source: Dragør's local climate strategy)

Jørgen Jensen adds:

"We are not interested in introducing too technical regulation of listed areas. We are working with the considerations for nature encapsulated in Natura 2000. We actually have a unique opportunity for creating natural physical coherence between coastal areas, forests and meadows, which also involves great opportunities for boosting the area's recreational assets."

Many interests combined in one watercourse

The same philosophy characterises how the municipality is aiming to tackle increasing amounts of surface water from the open countryside. In its green blue plan the municipality is planning an 'urban fringe zone' between Dragør and the neighbouring village of Store Magleby. This urban fringe zone is to be a buffer zone with recreational areas and areas where the water is delayed, can evaporate, or can percolate into the groundwater.

According to Jesper Horn Larsen, head of Teknik og Miljø (technical and environmental administration) in the municipality, there is actually a 'fast-flowing river' on Amager, named Hovedåen. It is situated along the municipal border and flows into Oresund. Hovedåen drains the relatively low-lying fields and, not least, Copenhagen Airport and Dragør. So far, the municipality has managed Hovedåen as a purely mechanical watercourse, an outflow watercourse able to collect surface water from drains.

The watercourse Hovedåen, which runs straight like a ruler through the landscape from Copenhagen Airport to Oresund, plays a pivotal role in Dragør's spatial planning of its open countryside.

"Lately, there has been more rain than the river can hold, which has resulted in flooding and claims for compensation from landowners; for who is to bear responsibility that the watercourse cannot cope with the increasing amount of water? The municipality cannot keep on excavating the watercourse to make it bigger, and we will soon have to live up to legislative environmental targets for the condition and quality of our watercourses. This will concretise the debate," says Jesper Horn Larsen.

"What we are considering at the moment is for the watercourse to be small when there isn't much water and bigger when there is. In extreme situations, fields which have been taken out of operation will serve as relief, they will be wet meadows where the water can accumulate," says Jesper Horn Larsen. Mr Horn Larsen stresses that many of these ideas are still on the drawing board, and that a debate with both citizens and landowners is needed before the right solutions can be found.